baby fish hiding under the bell of a jellyfish and using its stinging threads as protection from circling predators. this “floating safe house” will provide the fish with protection and food until they’re big enough to venture out on their own. (source)

It’s not a cephalopod or a cell but it’s PRETTY COOL

IT’S REALLY ADORABLE OH MAN A_A

oh my gosh it’s like something out of ghibli

hugfish

Tag: nice

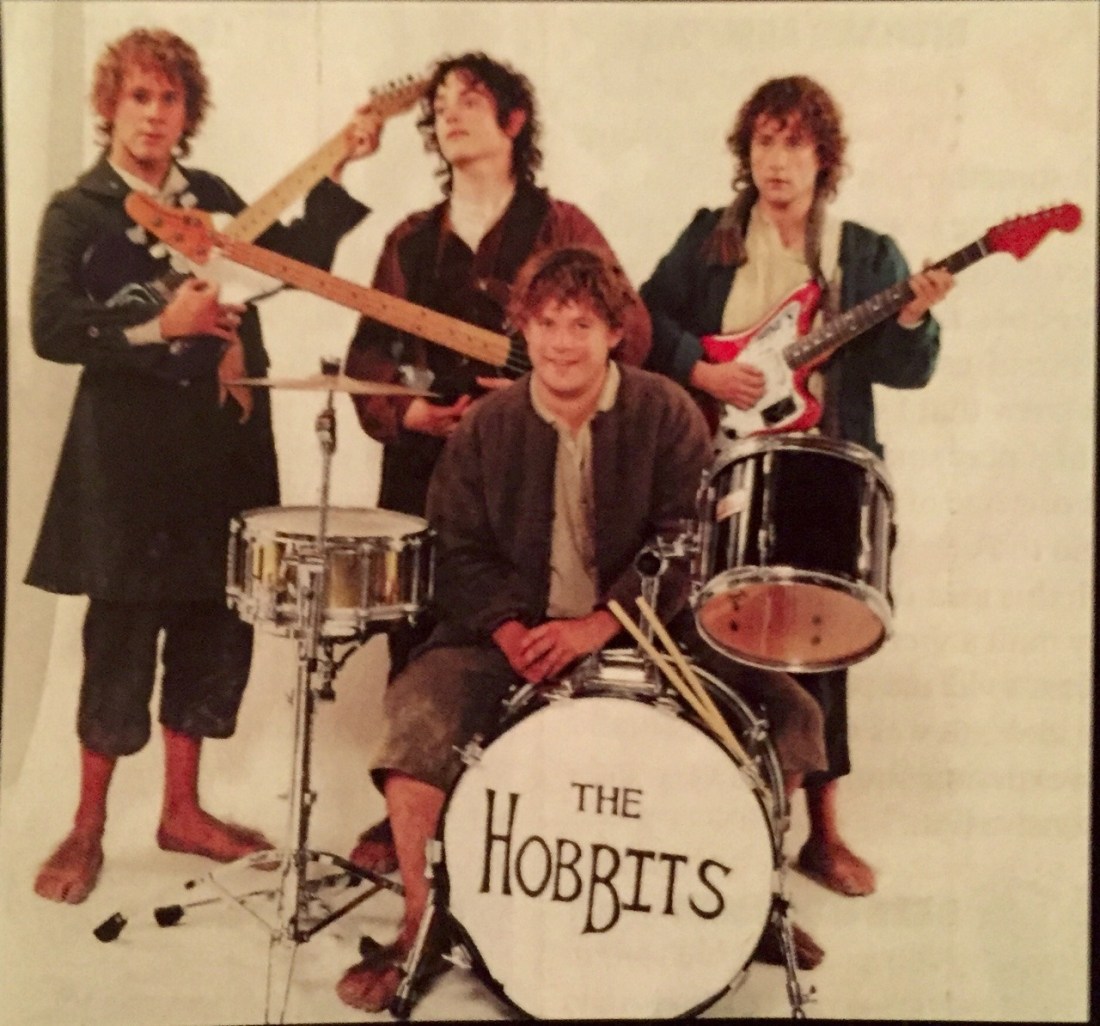

A birthday card that Elijah, Sean, Dom and Billy gave to Peter Jackson (while making The Lord of the Rings)

Did you know reindeers’ eyes change colour with Arctic seasons?

Researchers have discovered the eyes of Arctic reindeer change colour through the seasons from gold to blue (see top image), adapting to extreme changes of light levels in their environment and helping detect predators.

The BBSRC-funded team from UCL (University College London), and the University of Tromsø, Norway, showed that the colour change helps reindeer to see better in the continuous daylight of summer and continuous darkness of Arctic winters, by changing the sensitivity of the retina to light.

Top image copyright: Glen Jeffery

Bottom image copyright: Erling Nordoy

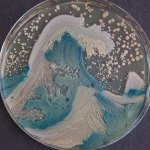

Microbiologists Create ‘Starry Night’ And Other Art With Bacteria For First Microbe Art Competition

American Society for Microbiology | microbeworld.org | Facebook

SEE THE LEGENDS

The American Society for Microbiologists

recently hosted its first international ‘Agar Art’ challenge in which

microbiologists from around the world used various microbes and germs to

create beautiful works of art in petri dishes. The submissions included

recognizable paintings like Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’ as well as

original microbe paintings.The scientists used nutritious agar

jelly as a “canvas” for their colorful microbes. While they do add an

element of randomness as they grow, they can also do things that paint

cannot – some of them emit bioflourescent light under certain

conditions, while others, guided by the scientists, grew into perfect

tree-branch patterns or jelly-fish tentacles.For more about the process behind art like this, read about the work of Tasha Sturm, a microbiologist who used an agar dish to capture the germs on an eight-year-old boy’s hand. Source: boredpanda

The tardigrade genome has been sequenced, and it has the most foreign DNA of any animal

Scientists have sequenced the entire genome of the tardigrade, AKA the water bear, for the first time. And it turns out that this weird little creature has the most foreign genes of any animal studied so far – or to put it another way, roughly one-sixth of the tardigrade’s genome was stolen from other species. We have to admit, we’re kinda not surprised.

A little background here for those who aren’t familiar with the strangeness that is the tardigrade – the microscopic water creature grows to just over 1 mm on average, and is the only animal that can survive in the harsh environment of space. It can also withstand temperatures from just above absolute zero to well above the boiling point of water, can cope with ridiculous amounts of pressure and radiation, and can live for more than 10 years without food or water. Basically, it’s nearly impossible to kill, and now scientists have shown that its DNA is just as bizarre as it is.

So what’s foreign DNA and why does it matter that tardigrades have so much of it? The term refers to genes that have come from another organism via a process known as horizontal gene transfer, as opposed to being passed down through traditional reproduction.

Horizontal gene transfer occurs in humans and other animals occasionally, usually as a result of gene swapping with viruses, but to put it into perspective, most animals have less than 1 percent of their genome made up of foreign DNA. Before this, the rotifer – another microscopic water creature – was believed to have the most foreign genes of any animal, with 8 or 9 percent.

But the new research has shown that approximately 6,000 of the tardigrade’s genes come from foreign species, which equates to around 17.5 percent.

“We had no idea that an animal genome could be composed of so much foreign DNA,” said study co-author Bob Goldstein, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We knew many animals acquire foreign genes, but we had no idea that it happens to this degree.”

https://vine.co/v/OPxenZQDLDh/embed/simple//platform.vine.co/static/scripts/embed.js

so….Jack and Bitty huh….

this moth is a fucking biohacker and if thats not the coolest shit you’ve ever heard get the fuck out of my face